[Note: This article was originally published in the March 8, 2024, print issue of Colorado Politics; a longer version was published March 11 on their website. Longer website version reprinted here with permission.]

The Colorado Judicial Institute is a 45-year-old nonprofit originally founded to focus on the state's relatively new system of appointing and retaining judges, which voters enacted to replace partisan judicial elections.

Now, CJI's work also includes advocating on behalf of the judiciary, informing the public about the courts and supporting the continuing education of judges.

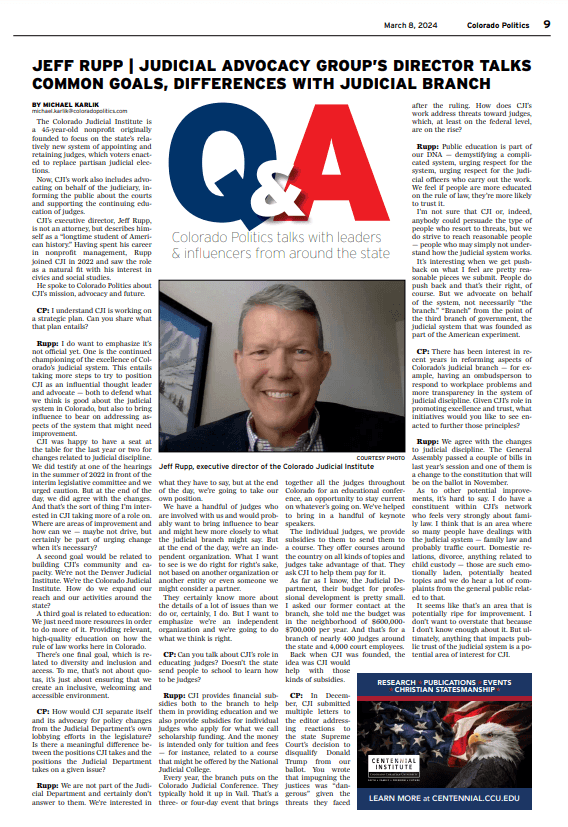

CJI's executive director, Jeff Rupp, is not an attorney, but describes himself as a "longtime student of American history." Having spent his career in nonprofit management, Rupp joined CJI in 2022 and saw the role as a natural fit with his interest in civics and social studies.

He spoke to Colorado Politics about CJI's mission, advocacy and future.

FAST FACTS:

• Jeff Rupp became the Colorado Judicial Institute's executive director in 2022. He is also an alpine skier and youth rugby coach.

• The Colorado Judicial Institute, founded in 1979, focuses on public education and advocacy about Colorado's judicial selection and retention system, and the work of the courts more broadly.

Colorado Politics: To your knowledge, is there an equivalent of the Colorado Judicial Institute in other states? If not, are you aware of how judicial education and advocacy happen elsewhere?

Jeff Rupp: I'm not aware of similar organizations to CJI in other states. I feel CJI is more of, or we aspire to be more of, a community organization, with more of an emphasis on public education.

There's a judge, she's a retired judge in Arizona, who reached out and I had a nice conversation with her. She was curious about CJI based on her experience. My understanding is Arizona has a similar judicial merit selection process and one worth defending. I think she perceived there might be threats. We live in more partisan times, so I suppose that's not surprising.

My understanding is that many, many years ago, people within CJI's governance had the idea that they wanted to export what we do to other states and sort of serve as a model. But I think they quickly figured out that we're just not resourced to be able to do that.

CP: I understand CJI is working on a strategic plan. Can you share what that plan entails?

Rupp: I do want to emphasize it's not official yet. One is the continued championing of the excellence of Colorado's judicial system. This entails taking more steps to try to position CJI as an influential thought leader and advocate — both to defend what we think is good about the judicial system in Colorado, but also to bring influence to bear on addressing aspects of the system that might need improvement.

CJI was happy to have a seat at the table for the last year or two for changes related to judicial discipline. We did testify at one of the hearings in the summer of 2022 in front of the interim legislative committee and we urged caution. But at the end of the day, we did agree with the changes. And that's the sort of thing I'm interested in CJI taking more of a role on. Where are areas of improvement and how can we — maybe not drive, but certainly be part of urging change when it's necessary?

A second goal would be related to building CJI's community and capacity. We're not the Denver Judicial Institute. We're the Colorado Judicial Institute. How do we expand our reach and our activities around the state?

A third goal is related to education: We just need more resources in order to do more of it. Providing relevant, high-quality education on how the rule of law works here in Colorado.

There's one final goal, which is related to diversity and inclusion and access. To me, that's not about quotas, it's just about ensuring that we create an inclusive, welcoming and accessible environment.

CP: How would CJI separate itself and its advocacy for policy changes from the Judicial Department's own lobbying efforts in the legislature? Is there a meaningful difference between the positions CJI takes and the positions the Judicial Department takes on a given issue?

Rupp: We are not part of the Judicial Department and certainly don't answer to them. We're interested in what they have to say, but at the end of the day, we're going to take our own position.

We have a handful of judges who are involved with us and would probably want to bring influence to bear and might hew more closely to what the judicial branch might say. But at the end of the day, we're an independent organization. What I want to see is we do right for right's sake, not based on another organization or another entity or even someone we might consider a partner.

They certainly know more about the details of a lot of issues than we do or, certainly, I do. But I want to emphasize we're an independent organization and we're going to do what we think is right.

CP: Can you talk about CJI's role in educating judges? Doesn't the state send people to school to learn how to be judges?

Rupp: CJI provides financial subsidies both to the branch to help them in providing education and we also provide subsidies for individual judges who apply for what we call scholarship funding. And the money is intended only for tuition and fees — for instance, related to a course that might be offered by the National Judicial College.

Every year, the branch puts on the Colorado Judicial Conference. They typically hold it up in Vail. That's a three- or four-day event that brings together all the judges throughout Colorado for an educational conference, an opportunity to stay current on whatever’s going on. We've helped to bring in a handful of keynote speakers.

The individual judges, we provide subsidies to them to send them to a course. They offer courses around the country on all kinds of topics and judges take advantage of that. They ask CJI to help them pay for it.

As far as I know, the Judicial Department, their budget for professional development is pretty small. I asked our former contact at the branch, she told me the budget was in the neighborhood of $600,000-$700,000 per year. And that's for a branch of nearly 400 judges around the state and 4,000 court employees.

Back when CJI was founded, the idea was CJI would help with those kinds of subsidies.

CP: In December, CJI submitted multiple letters to the editor addressing reactions to the state Supreme Court's decision to disqualify Donald Trump from our ballot. You wrote that impugning the justices was "dangerous" given the threats they faced after the ruling. How does CJI's work address threats toward judges, which, at least on the federal level, are on the rise?

Rupp: Public education is part of our DNA — demystifying a complicated system, urging respect for the system, urging respect for the judicial officers who carry out the work. We feel if people are more educated on the rule of law, they're more likely to trust it.

I'm not sure that CJI or, indeed, anybody could persuade the type of people who resort to threats, but we do strive to reach reasonable people — people who may simply not understand how the judicial system works.

It's interesting when we get pushback on what I feel are pretty reasonable pieces we submit. People do push back and that's their right, of course. But we advocate on behalf of the system, not necessarily "the branch." "Branch" from the point of the third branch of government, the judicial system that was founded as part of the American experiment. [Editor's note: Misquote, should have read "But we advocate on behalf of the judicial system, not necessarily "the branch." "Branch" in the sense of Colorado's judicial department."]

CP: There has been interest in recent years in reforming aspects of Colorado's judicial branch — for example, having an ombudsperson to respond to workplace problems and more transparency in the system of judicial discipline. Given CJI's role in promoting excellence and trust, what initiatives would you like to see enacted to further those principles?

Rupp: We agree with the changes to judicial discipline. The General Assembly passed a couple of bills in last year's session and one of them is a change to the constitution that will be on the ballot in November.

As to other potential improvements, it's hard to say. I do have a constituent within CJI's network who feels very strongly about family law. I think that is an area where so many people have dealings with the judicial system — family law and probably traffic court. Domestic relations, divorce, anything related to child custody — those are such emotionally laden, potentially heated topics and we do hear a lot of complaints from the general public related to that.

It seems like that's an area that is potentially ripe for improvement. I don't want to overstate that because I don't know enough about it. But ultimately, anything that impacts public trust of the judicial system is a potential area of interest for CJI.

CP: The CJI holds a gala every year where it honors judicial excellence (Colorado Politics' parent company is a sponsor). From CJI's perspective, what are some of the exemplary practices you've seen judges exhibit that you wish others would emulate statewide? And on the flip side, are there any trends or longstanding habits in the judiciary that CJI would discourage judges from perpetuating — again, in order to further the goals of judicial excellence and trust?

Rupp: Yeah, there are several exemplary traits that we see in the nominations each year. It goes beyond what you typically see in what would be good or exemplary performance evaluations conducted by the performance commissions, where they look at legal knowledge and management of one's docket and demeanor and that kind of thing.

A couple of years ago, we brought a keynoter to the judicial conference, a judge from New Jersey, who practiced "procedural justice" — really, the focus on the dignity and respect for the people in the courtroom. It's not about the judge, it's about the litigants.

There is a story I'll share about one of our awardees from last fall, (Adams County Court) Judge Mariana Vielma. Apparently, there was a hard-of-hearing defendant in the courtroom and when the judge recognized the defendant was having difficulty with the hearing device he was using, Judge Vielma actually left the bench to stand next to the man to ensure he could understand what was going on.

That's really remarkable. How many judges would think to do that, much less actually do it? It's the showing of the genuine human connection, the compassion and even a certain humility. Truly seeing somebody and the problem they're having and going beyond, while maintaining the decorum of the courtroom.

On the flip side: lack of preparation. Not being willing to ask for help. We know some judges are overwhelmed with their dockets. They need to be able to ask for help. You can't get overwhelmed and just slow down. Losing control of the courtroom, losing control of one's temper, one's patience. Harassment — we all know that's what led to the changes in judicial discipline.

There's one last thing and this is my own opinion. It's interesting to me because I came to CJI without a background in the legal system — it's not a negative trait, but it's the question of how judges might insist on being addressed outside of the courtroom. We're all so used to being deferential to judges, calling them "judge" or "justice," but in settings outside the courtroom, I wonder about that.

I wonder if that expectation of deferential treatment through the use of the title, is that really necessary or productive? Does that promote approachability? Does it prevent people from seeing judges as human, too?

It's a mixed bag. Some judges are very humble and quick to say, "Call me by my first name." I'm talking about outside of the courtroom, in a community setting. There are others I've encountered who are more insistent on the use of the title. For me, it is something worth considering because, going back to CJI, it is about promoting public trust. I think approachability and humanization of judges can help with public trust.